Expository Writing

“Write” is a frequent, yet complex task that is often assigned to students in school. Whether telling a story, writing a science lab report, or answering short-answer questions in social studies, students are asked to write in just about every subject throughout the day. Despite the pervasive nature of writing in all areas of education, it is one of the most complex tasks that students are asked to complete. It may seem like a simple task, but it is full of many hidden demands. The place students most commonly learn to write is language arts or English class, and expository writing is the primary focus. Expository writing explains, describes, and gives information using evidence, details, and facts to support a specific topic. To help students gain confidence in their own writing, master the many hidden demands, and grow their skills, the levels of expository writing sophistication should be taught using a scaffolded hierarchy. This progression of skills is especially helpful for those with language-based learning disabilities.

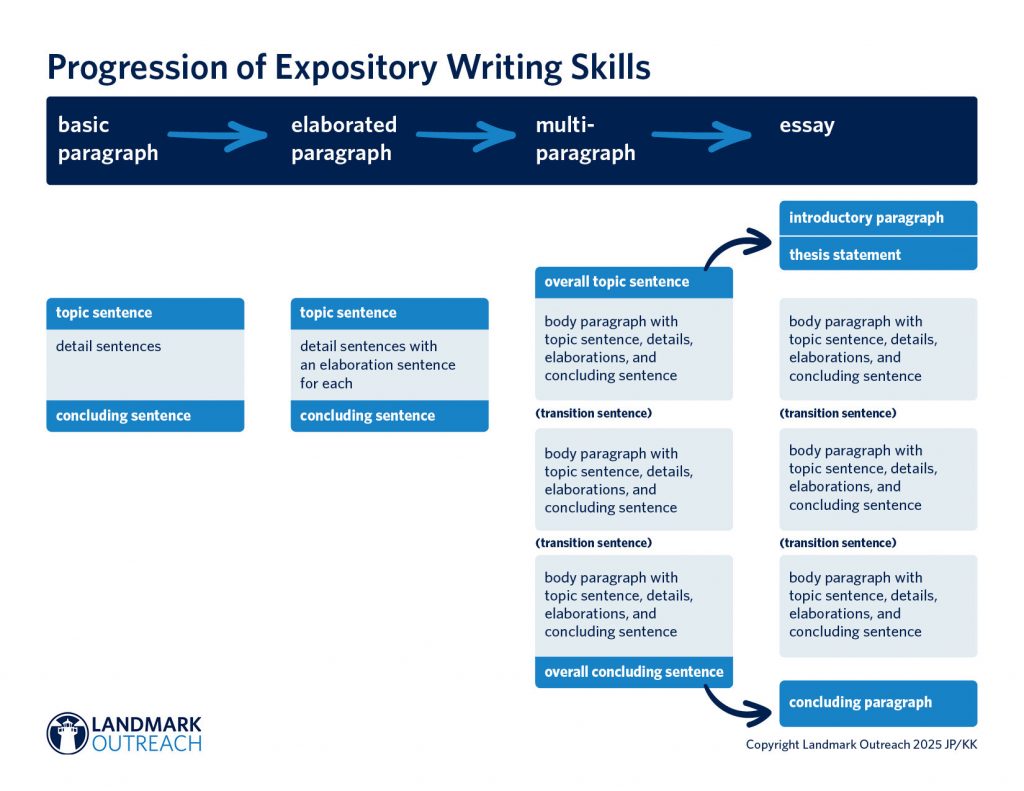

As students master the essential skills at one level of the writing hierarchy, they are ready to be challenged by the new skills introduced at the next level. The logic behind following this progression of writing skills is to minimize the number of new skills being learned while continuously practicing previously learned skills to ensure automatization.

The basic paragraph is the initial level of the expository writing hierarchy. At this stage, students learn that a paragraph must have a topic sentence, detail sentences (i.e., evidence or examples related to the topic) to support that topic sentence, and a concluding sentence to tie it all together. Instruction focuses on narrowing a topic and choosing relevant information, a.k.a. details, to expand on it. Although there is no specific number of details that is required to make a paragraph, three tends to be the magic number that provides adequate support while still remaining focused on the topic. Once these basic skills have been mastered, students can be introduced to elaborated paragraph structure, which adds the element of an elaboration for each detail. A 5-sentence paragraph can turn into 8 sentences by adding a sentence to provide more information about each detail. To help students add elaborations to their details, asking prompting questions (why? how? for example?) can help them elaborate without simply repeating the detail in different words.

When a student has mastered an elaborated paragraph, they are then ready to start stringing paragraphs together. Multi-paragraph writing encourages students to continue practicing elaborated paragraph structure while learning to subdivide a topic further and string paragraphs on the same topic together into a composition. Since each paragraph requires its own topic sentence, one of the new skills introduced at this level is how to write an overall topic sentence that expresses the focus of the entire composition. An overall topic sentence introduces the focus of the entire composition, the idea that ties the paragraphs together. It is placed at the beginning of the first paragraph before that paragraph’s topic sentence. Similarly, an overall concluding sentence, which is the last sentence in the final paragraph, wraps up the entire piece, summarizing the main point of the entire composition. Additionally, students will need to learn to write transition sentences to link each paragraph to the one that follows. Teaching transition sentences is an excellent opportunity to provide instruction in compound sentences, since they can make straightforward and clear transition sentences in compositions. For example, if one paragraph in a composition about extracurricular activities is about the arts and the next one is about athletics, the transition sentence could be as follows: Although after school art is beneficial for many students, others enjoy participating in athletics.

Multi-paragraph compositions are an essential step on the way to essay writing. Essays require introduction paragraphs, thesis statements, and concluding paragraphs. Without this essential level of the hierarchy, students would have to jump from writing elaborated paragraphs straight to writing essays. Skipping multi-paragraph writing would force educators to cover the new elements of an essay, as well as teach transition sentences, which can present an overwhelming leap in expectations for students who struggle with writing. After learning to compose a strong multi-paragraph composition, the overall topic sentence can become the basis of a thesis statement, and the overall concluding sentence the beginning of a solid conclusion paragraph. Since students would have learned to transition between paragraphs at the multi-paragraph level, moving on to essay writing after this step allows teachers to focus on honing these two added paragraphs, demonstrating how they relate to previously learned skills.

Walking students through mastery of each of these levels of the hierarchy of expository writing provides a clear path to confidence in their own writing abilities. By slowly adding bigger challenges to overcome and guiding them as they learn new skills, all students can become strong writers. By slowly increasing the challenge of writing tasks and guiding students as they learn new skills, the complex, multistep nature of writing is made visible for students, and the request to “write” becomes less daunting.