“If you don’t know where you’re going, you’ll end up someplace else” (Yogi Berra).

For many students, the struggle begins when they are assigned a paper, project, or presentation. They may be overwhelmed by the enormity of the task, or not know where to start. Others may dive right in, but without a clear plan, the final result will likely be disorganized, unfinished, or not reflective of their true understanding. As Yogi Berra notes, they end up somewhere quite different from where they started.

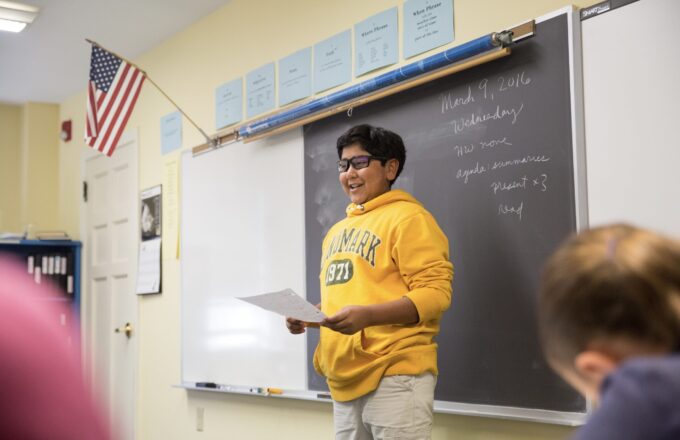

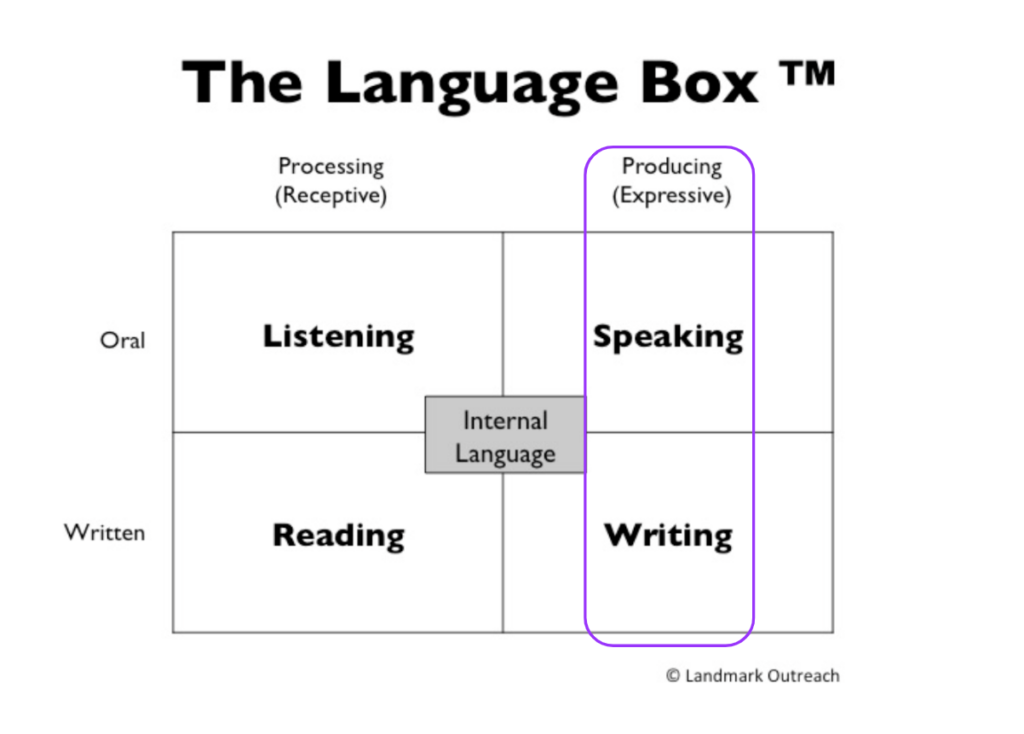

In our previous roles as the Director and Assistant Director of the Expressive Language (EL) Program at Landmark High School, we worked with students with a primary diagnosis of specific learning disability in reading, writing, or math (also called LBLD, or a language-based learning disability). Students placed in the EL Program face the compounded obstacle of expressive language weaknesses alongside their primary diagnosis, which further hampers their abilities in writing and speaking. While these students have strengths in their receptive language skills (processing), they often present ›with difficulty and frustration in expressing what they know through speaking and writing (producing).

In our previous roles as the Director and Assistant Director of the Expressive Language (EL) Program at Landmark High School, we worked with students with a primary diagnosis of specific learning disability in reading, writing, or math (also called LBLD, or a language-based learning disability). Students placed in the EL Program face the compounded obstacle of expressive language weaknesses alongside their primary diagnosis, which further hampers their abilities in writing and speaking. While these students have strengths in their receptive language skills (processing), they often present ›with difficulty and frustration in expressing what they know through speaking and writing (producing).

In class activities, the students’ oral and written output may include circumlocutions, simple sentence structure, basic vocabulary, and lack of elaboration. Their ideas may also be out of order or unfinished, and students have difficulty retrieving desired words. When asked to complete a larger assignment like a composition or oral presentation, students with expressive language deficits will need highly structured, explicit guidance to know where to start and to ensure that they work towards a finished product that accurately “shows what they know.”

A Guided Process Approach

Students with expressive language weaknesses benefit from a guided, process-driven approach to overcome language difficulties across the five parameters of language (phonology, morphology, syntax, semantics, and discourse/pragmatics) and improve both the quality and independence of their output over time. To support students’ formulation of language to tackle assignments like papers and oral presentations, teachers should follow a micro-united approach.

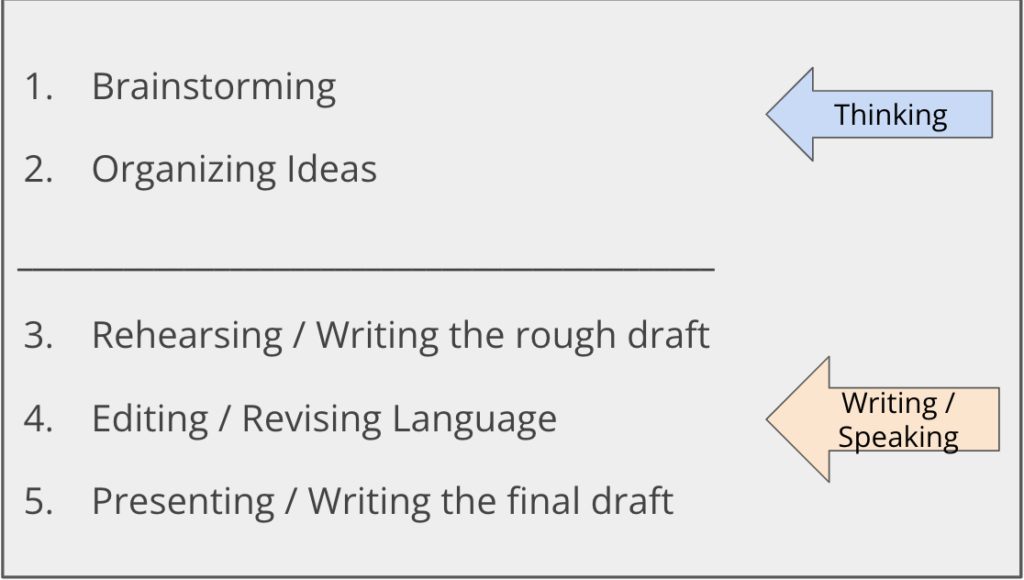

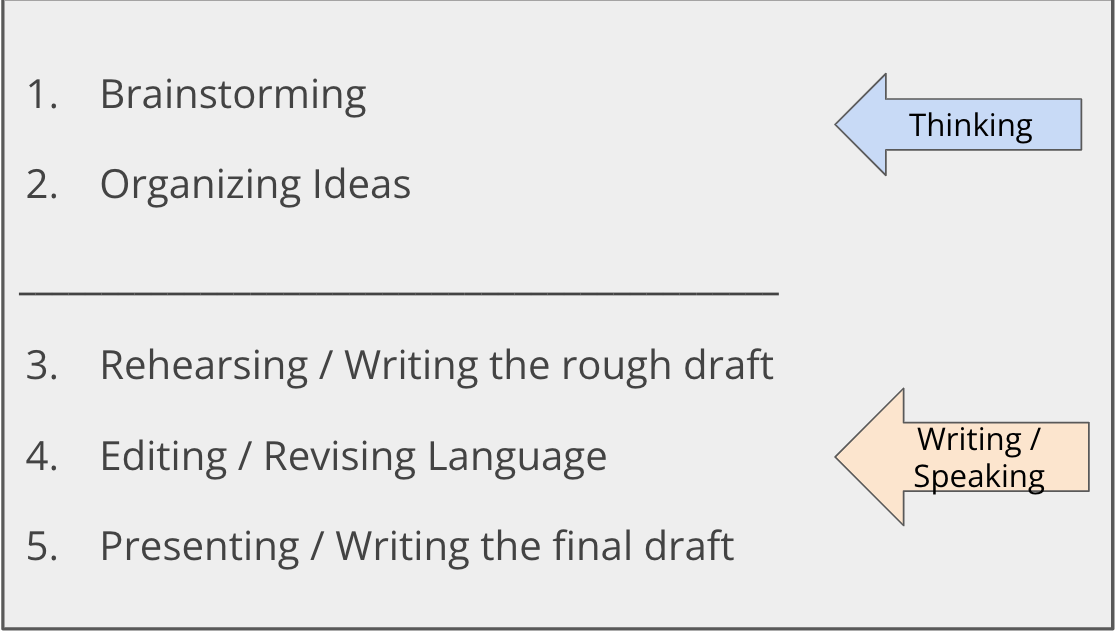

For writing and formal oral language tasks at Landmark, we follow a five-step process, which more broadly occurs in two distinct phases. The prewriting/planning phase is all about idea-building, and includes the initial brainstorm of ALL ideas, followed by narrowing down and sequencing them using a structured graphic organizer. The writing/production phase starts with a rough draft in full sentences, followed by self-review or proofreading for content and syntax, then culminating with the final product (polished draft or presentation). It’s important to emphasize with students that all of the same tools, scaffolds, and supports can be applied to both oral and written language tasks, as they (generally) follow the same structure.

Collaborative Planning: The Thinking Phase for Speaking & Writing

Students will be most successful when they are guided through the planning process of an assignment. Teachers can support working memory, word retrieval, and processing speed deficits with specific strategies.

Prompt Analysis

First, engage students in the process of initiation by collaboratively breaking down a question or analyzing a prompt using metacognitive strategies.

To analyze the prompt, model self-talk:

- What is being asked of me?

- What kind of language is expected?

- What evidence do I need to include?

- How will I know if I have met the expectation?

Brainstorm

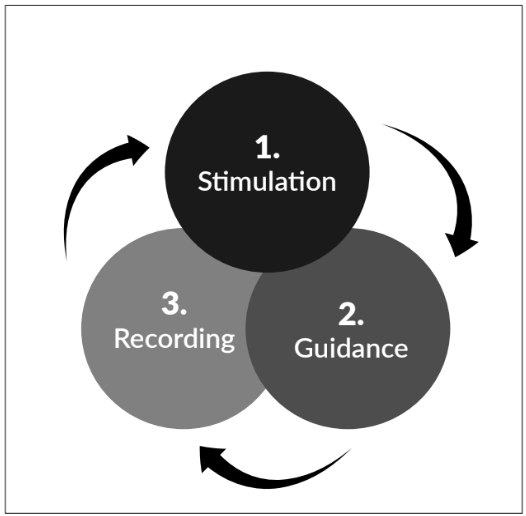

Once the task is clear, teachers can set students up for success by guiding them through the brainstorming phase. Jennings & Haynes (2018) note, “Brainstorming is a teaching method for activating students’ prior knowledge of concepts and vocabulary related to a topic. Brainstorming employs a cycle of three overlapping and sequential phases: stimulation, guidance, and recording.”

During the stimulation phase, it is important to engage students’ prior knowledge. Teachers can show videos and images to support the prompt. During the guidance phase, the use of cueing strategies will allow students with expressive language deficits to recall concepts and retrieve specific vocabulary.

These are the most common cueing strategies, ordered by the greatest demand on students’ retrieval abilities:

- Gestural → pointing up to elicit the word increase

- Pictorial → show an image of a house to elicit the word abode

- Semantic → teacher says “the opposite of deep” to elicit the word shallow

- Phonemic → teacher says “starts with an /b/ sound” to elicit the word button

- Orthographic → teacher writes the first syllable cat to elicit the word caterpillar

During the recording phase, teachers should validate all students’ responses by writing them on the board.

Organize

The “organize” step tasks students to narrow their focus and categorize the ideas they brainstormed as a group, and then individually, into main ideas and corresponding details.

At this stage, teachers provide specific tools (such as graphic organizers) to help structure conversations about logically ordering ideas, as well as eliminating less relevant points and combining similar ones. Teachers can support throughout the assignment by modeling metacognition and reminding students that the “organize” step still lives within the “idea phase” of the process. By limiting the scope to phrase-level concepts rather than complete sentences, teachers provide students with the cognitive space they need to be successful at this stage.

The organizing step can look different depending on the assignment and the individual’s preference. Teachers can provide additional scaffolds, such as word banks, to help students draw on previously learned skills. Also, students may benefit from prompting questions or having portions of a template pre-filled as they become more familiar with the tool. Exposing students to the different formats through structured, guided practice helps them identify which tools work best for them so they can put them to regular use. Ideally, teachers should model the entire process by engaging students in group brainstorming and organizing prior to releasing them to individual work.

Oral Rehearsal

Students with expressive language weaknesses especially benefit from oral rehearsal. Specifically for expository language tasks, this oral practice helps develop internal language to strengthen writing skills. Benefits of incorporating this strategy during discourse include:

- Promoting thinking and analytical skills

- Clarifying concepts and correcting misconceptions

- Identifying new information

- Linking topics

- Organizing thoughts

- Facilitating collaboration

Including Students in the Process

Students want to get right down to business when we ask them to start a project, whether it’s a writing task or a formal oral presentation. For students with expressive language deficits, teachers need to highlight the importance of slowing down and following a process approach that clearly incorporates thinking, reflecting, and planning. When given support to engage in effective brainstorming and organizing, students experience relief at having a clear plan when it is time to produce their draft. Eventually, after repetition and practice, students will begin to internalize the strategies that work for them and more confidently produce language that actually shows what they know.

References

Jennings, T. M., & Haynes, C. W. (2018). From talking to writing: Strategies for supporting narrative and expository writing. Landmark School Outreach Program.