Redefining Writing

Similar to studying for a test or doing a lab report, writing essays is just another classic educational requirement that students expect, expect to dislike, and try to avoid. These assignments ask students to showcase skills through actions that involve steps. Of course, writing lab reports and essays is not inherently fun, but that is not why students shiver every time a teacher displays a prompt on the board with a deadline. Writing an essay is hard but so is buying a house, learning how to drive a stick shift, and making a fancy dinner for a date. However, “smaller” tasks such as looking for potential homes in a desired area on Zillow, learning exactly where the clutch is in your older brother’s Honda Civic, and boiling water on the stove are all less daunting than the end results previously listed. From a student’s perspective, it seems counterintuitive to be the recipient of “more work” when the initial task seemed so gargantuan in the first place. However, if we can model, practice, and require students to engage with this thought process, then we can help them flex their metacognitive muscles and help them redefine challenging academic feats beyond just writing.

At Landmark School, students are required to follow a five-step writing process. In order to create checks and balances as ideas evolve into written language, we approach the writing process with the following: brainstorming, organizing, composing a rough draft, proofreading, and making final edits before turning it in. Breaking a daunting task like writing an essay into areas of specialized focus and attention minimizes the stress of tackling a large assignment by focusing efforts on smaller, more manageable steps in real time.

The images below are links to PDF documents for your reference.

| Step #1: Brainstorm |

Creating a brainstorming activity is the most essential. Students share their ideas in an unstructured space, usually collectively, so all can benefit from the various perspectives. Helping students get their unstructured ideas and understanding down can be an effective strategy for anyone who is struggling with procrastination because it results in productive action. Effective brainstorming also encourages students to analyze the prompt so they have a clear understanding of the task for writing. The sample brainstorm sheet encourages students to consider various aspects of the prompt: Are there unknown words that need to be defined? Which part of the prompt may be laying groundwork vs. asking the question? How long does it need to be? How should ideas be subdivided for future paragraphs? Creating a basic visual space, like a table that can grow with text, along with questions that cue the writer to reference the prompt, can provide incentive and direction to set an appropriate and constructive foundation. Creating a brainstorming activity is the most essential. Students share their ideas in an unstructured space, usually collectively, so all can benefit from the various perspectives. Helping students get their unstructured ideas and understanding down can be an effective strategy for anyone who is struggling with procrastination because it results in productive action. Effective brainstorming also encourages students to analyze the prompt so they have a clear understanding of the task for writing. The sample brainstorm sheet encourages students to consider various aspects of the prompt: Are there unknown words that need to be defined? Which part of the prompt may be laying groundwork vs. asking the question? How long does it need to be? How should ideas be subdivided for future paragraphs? Creating a basic visual space, like a table that can grow with text, along with questions that cue the writer to reference the prompt, can provide incentive and direction to set an appropriate and constructive foundation.

|

|

| Step #2: Organization |

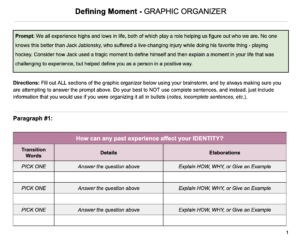

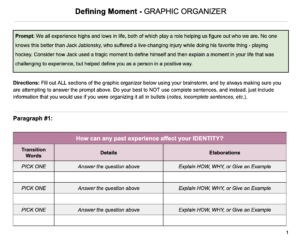

To help students transition from the ideas in their brainstorm into a more formalized outline, provide them with a graphic organizer that is tailored to what the prompt is asking in terms of length and content. Using color, shapes, lines, boxes, and cues can support students with vetting information to keep in their essays and support them with the sequencing of ideas. For instance, the sample shows a graphic organizer with a table that has two columns and three rows. As the student fills in each box in the table, the boxes grow as more writing is produced. Labeled boxes can also be included on the top and the bottom of the table for students to identify the main idea of their paragraph, which will eventually evolve into a topic sentence as well as a place for concluding ideas underneath. This basic structure is a foundation that can be adapted for greater length with ease by making copies of the table. Tables can also be rearranged and added when quotes are involved, when the structure of the essay changes, or when specialized paragraphs like an intro and conclusion are needed. To help students transition from the ideas in their brainstorm into a more formalized outline, provide them with a graphic organizer that is tailored to what the prompt is asking in terms of length and content. Using color, shapes, lines, boxes, and cues can support students with vetting information to keep in their essays and support them with the sequencing of ideas. For instance, the sample shows a graphic organizer with a table that has two columns and three rows. As the student fills in each box in the table, the boxes grow as more writing is produced. Labeled boxes can also be included on the top and the bottom of the table for students to identify the main idea of their paragraph, which will eventually evolve into a topic sentence as well as a place for concluding ideas underneath. This basic structure is a foundation that can be adapted for greater length with ease by making copies of the table. Tables can also be rearranged and added when quotes are involved, when the structure of the essay changes, or when specialized paragraphs like an intro and conclusion are needed.

|

|

| Step #3: Rough Draft |

Guiding students from their structured graphic organizer to create a rough draft should follow the road map outlined in the organizer. At this stage, students turn the ideas in their graphic organizer into formal, smooth, concise, and clear written language which can be an added difficulty for students with dyslexia. Creating a color-coded rough draft template that matches the previously used outline graphic organizer can help students retain the structure and sequence of their outline when they convert ideas into sentences and then paragraphs. Include in this version what kind of sentences need to be included: topic sentence, detail, elaboration, or concluding sentence. Using consistent colors assists students who may struggle with keeping their ideas in order. Once they fill out each table with a sentence for each idea in the graphic organizer, they simply copy and paste them onto a blank doc in the same order, thus producing something that visually appears to be an essay. As you can see in the example, it is also useful to include the prompt at the top of each step, especially to reinforce how important it is to always be “proving something,” especially as ideas take shape into formal language in this step. Guiding students from their structured graphic organizer to create a rough draft should follow the road map outlined in the organizer. At this stage, students turn the ideas in their graphic organizer into formal, smooth, concise, and clear written language which can be an added difficulty for students with dyslexia. Creating a color-coded rough draft template that matches the previously used outline graphic organizer can help students retain the structure and sequence of their outline when they convert ideas into sentences and then paragraphs. Include in this version what kind of sentences need to be included: topic sentence, detail, elaboration, or concluding sentence. Using consistent colors assists students who may struggle with keeping their ideas in order. Once they fill out each table with a sentence for each idea in the graphic organizer, they simply copy and paste them onto a blank doc in the same order, thus producing something that visually appears to be an essay. As you can see in the example, it is also useful to include the prompt at the top of each step, especially to reinforce how important it is to always be “proving something,” especially as ideas take shape into formal language in this step.

|

|

|

| Step #4: Proofreading |

The conversion process from ideas to sentences is likely to produce some bumps in the road, so proofreading is essential. Selling this step of the process is no easy task, though, so it is paramount to create an assignment that forces accountability. I like to create a checklist on a Google Doc that encourages students to proofread with action. This means that they may proofread one paragraph at a time, or you can choose to have them proofread for content one night and then form and structure the following night. This way, they can have greater focus on certain elements of their writing and it also encourages them to reread their essay more with a critical lens. Google Docs has a great feature now for adding bullets that work as checked boxes so once the box is checked, the line following it is struck through. It is also helpful to add these in front of the actions you are requiring such as, “bold all of your transition words” because once they finish the task, they can check the box and feel the reward of completing something. The conversion process from ideas to sentences is likely to produce some bumps in the road, so proofreading is essential. Selling this step of the process is no easy task, though, so it is paramount to create an assignment that forces accountability. I like to create a checklist on a Google Doc that encourages students to proofread with action. This means that they may proofread one paragraph at a time, or you can choose to have them proofread for content one night and then form and structure the following night. This way, they can have greater focus on certain elements of their writing and it also encourages them to reread their essay more with a critical lens. Google Docs has a great feature now for adding bullets that work as checked boxes so once the box is checked, the line following it is struck through. It is also helpful to add these in front of the actions you are requiring such as, “bold all of your transition words” because once they finish the task, they can check the box and feel the reward of completing something.

|

|

| Step #5: Final Draft |

Now that they have completed four out of the five steps, and their work takes the shape of an essay, students often think they are done. But instead of just asking them to reread their work one more time and turn it in, provide them with structured opportunities to actively check their work before submitting it. Students can check their citations and formatting or review the rubric and cross-check their own work. Posting examples of certain elements, whether it is a new skill being worked on or a review of a component that has a heavier focus on their grading rubric, are also ways for students to refine their work. Now that they have completed four out of the five steps, and their work takes the shape of an essay, students often think they are done. But instead of just asking them to reread their work one more time and turn it in, provide them with structured opportunities to actively check their work before submitting it. Students can check their citations and formatting or review the rubric and cross-check their own work. Posting examples of certain elements, whether it is a new skill being worked on or a review of a component that has a heavier focus on their grading rubric, are also ways for students to refine their work. |

|

This process needs to be introduced, modeled, and practiced from the get-go in order for its utility to be maximized. Then, over the course of the school year, the level of challenge and sophistication can progressively be increased without altering the number of steps, or the purpose of each. While most of the work supporting this process is creating buy-in and familiarity at the beginning of the year, the other challenge is creating materials to support student work and skill development. It can be time-consuming to create one’s own materials, but if a basic version of each step is initially created, adapting subsequent templates, organizers, checklists, and other documents can be developed easily. In this day and age, it is vital to include opportunities for students to upgrade their digital pedigree, especially in preparation for post-secondary opportunities and with the rise of A.I. Although balance is key, digital steps of the writing process can be created quickly, shared/delivered efficiently, monitored regularly, and graded seamlessly, especially when the Google Suite is employed because of how interconnected all their educational apps are.

Now that they have completed four out of the five steps, and their work takes the shape of an essay, students often think they are done. But instead of just asking them to reread their work one more time and turn it in, provide them with structured opportunities to actively check their work before submitting it. Students can check their citations and formatting or review the rubric and cross-check their own work. Posting examples of certain elements, whether it is a new skill being worked on or a review of a component that has a heavier focus on their grading rubric, are also ways for students to refine their work.

Now that they have completed four out of the five steps, and their work takes the shape of an essay, students often think they are done. But instead of just asking them to reread their work one more time and turn it in, provide them with structured opportunities to actively check their work before submitting it. Students can check their citations and formatting or review the rubric and cross-check their own work. Posting examples of certain elements, whether it is a new skill being worked on or a review of a component that has a heavier focus on their grading rubric, are also ways for students to refine their work.