What to Know

The development of fluent language skills is rooted in complex cognitive processes that include attention, auditory and visual perception and processing, memory, and executive function. Students who have difficulty in any of these areas may also have difficulty acquiring the facility with language that school requires. To understand a reading selection, for example, students must be able to pay attention to the task of reading, decode the words, retrieve vocabulary and related knowledge from memory, and recognize the syntax and structure of discourse.

The Basics

Language-based learning disability (LBLD) refers to a spectrum of difficulties related to the understanding and use of spoken and written language. LBLD is a common cause of students’ academic struggles because weak language skills impede comprehension and communication, which are the basis for most school activities.

Like all learning disabilities, LBLD results from a combination of neurobiological differences (variations in the way an individual’s brain functions) and environmental factors (e.g., the learning setting, the type of instruction). The key to supporting students with LBLD is knowing how to adjust curriculum and instruction to ensure they develop proficient language and literacy skills. Most individuals with LBLD need instruction that is specialized, explicit, structured, and multisensory, as well as ongoing, guided practice aimed at remediating their specific areas of weakness.

LBLD can manifest as a wide variety of language difficulties with different levels of severity. One student may have difficulty sounding out words for reading or spelling, but no difficulty with oral expression or listening comprehension. Another may struggle with all three. The spectrum of LBLD ranges from students who experience minor interferences that may be addressed in class to students who need specialized, individualized attention throughout the school day in order to develop fluent language skills.

Academic Proficiency

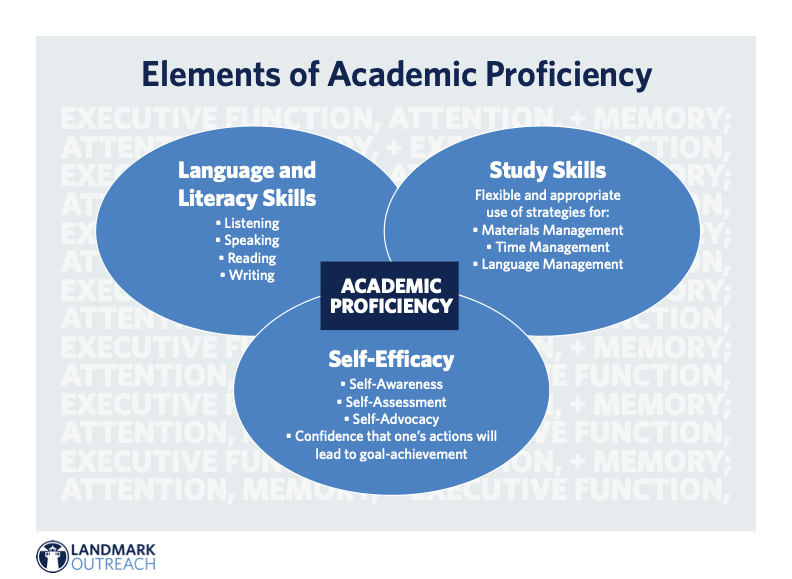

Academic proficiency develops in relation to students’ increasing skills and abilities. Its three interrelated elements, shown in Figure 1, are coordinated by the individual’s executive function. Executive function enables students to maintain focus, progress, and motivation; make connections with existing knowledge; recognize when comprehension falters; and apply strategies to modulate frustration and resolve lapses in understanding.

Language and literacy skills include listening, speaking, reading, and writing. Study skills include flexible and appropriate use of strategies for managing materials, time, and language. Self-efficacy (the belief that one’s actions are related to outcomes) includes skills in self-awareness, self-assessment, and self-advocacy. All of these skills are coordinated by executive function, which is the brain’s super-manager and empowers students to set goals, marshal the various internal and external resources needed to meet them, and make adjustments to ensure accomplishment.

Figure 1. Elements of Academic Proficiency

Most students with LBLD develop academic proficiency only when they are taught skills within a supportive environment of curriculum and instruction designed to meet their specific needs. When teachers know how to celebrate students’ strong skills and remediate their weak ones using skills-based curriculum and instruction, students’ lives can change. The first step to empowering students with LBLD is to understand how and when LBLD impacts their school experience and why language-based teaching works.

Emergence and Signs of Language-Based Difficulties

Children naturally develop skills at their own pace, and most students have difficulty learning from time to time. To assess whether a student’s performance in a skill area warrants concern, we must take into account typical development patterns. We expect preschool children to have difficulty tying their shoes, cutting out pictures from magazines, adding numbers, and writing neatly. Middle school students should be able to do these things quite easily. It is persistent difficulty in one or more skill areas that requires investigation. Even so, the level of struggle that calls for investigation does not emerge at a predictable time in child development; rather, difficulties may appear at any time from preschool through adulthood. Here are some common difficulties for students with LBLD:

| Academic Challenges: | Other Challenges: |

|

|

While some students with language-based learning disabilities are diagnosed very young, many other students progress through early elementary school with few issues. As they transition into middle school, high school, or even college, the demands for language rise, as do expectations for independent learning. Students who performed competently in structured, skills-based, supportive classrooms may find themselves floundering as they try to manage their schoolwork and homework with less individual guidance from teachers. They may suddenly seem anxious, frustrated, angry, or defeated about school. This level of change warrants investigation and should not automatically be attributed to typical adolescent behavior. Sometimes difficulties emerge because the compensatory strategies students used in the past stop working. Many bright students with learning disabilities go to great lengths to mask their struggles. Their intelligence enables them to compensate for lack of skill in one area with talents in other areas. A student might be a terrific talker and demonstrate solid knowledge in class discussions. Why would the teacher guess this student cannot read fluently? While students’ capacity to adapt is admirable, the cost is high. Too often, they enter middle and high school with elementary-level reading and writing skills.

Language Difficulty or Disability?

Language difficulties are not always language disabilities. In order for a student to be eligible for special education services guided by an individualized education plan (IEP), he or she must be diagnosed with a disability. Under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), a language-based learning disability is considered a specific learning disability (SLD). A diagnosis of SLD means the student’s difficulties are not the result of:

- Environmental, cultural, or economic disadvantage

- Difficulty acquiring English as a second language

- A motor disability

- A visual or hearing acuity problem

- Impaired cognitive function (though severe forms of LBLD can affect performance on assessment of cognitive function)

Student Profiles

Students have unique learning profiles shaped by their educational experiences, learning and thinking styles, personality traits, and specific needs related to language acquisition and use. All students who struggle in school—particularly those with LBLD—benefit from structured, multisensory, skills-based instruction. Each requires individualized instruction tailored to their specific needs.

The following student profiles highlight different aspects of five students: Lan, Carlos, Ayanna, Elijah, and Jason. Each faces challenges in school that teachers must analyze and address. These profiles are composites of several real students, with names changed for privacy.

As you read about each student’s background and current performance, keep in mind the following questions:

- Why might this student be struggling?

- What is preventing these students from learning effectively?

- What steps would you take to support this student?

LAN GRADE 2: She is the only child in a two-parent, English-speaking household in a small city. Her teacher is concerned about her reading, writing, math, and social skills. Lan’s reading skills fall significantly below grade level despite her work in a small, supportive reading group over the past two years. In writing, she demonstrates good penmanship and produces lengthy compositions; however, her spelling, vocabulary, syntax, and organization of ideas make her writing very difficult to understand. In math, she has good number sense but struggles with word and logic problems. Lan focuses intently on all her schoolwork and becomes angry when she makes mistakes or when teachers offer support or suggestions for improvement. Lan’s homework is always complete, and her hands-on projects demonstrate understanding of the concepts taught in class. Socially, Lan struggles. Though she seeks out others for play and projects, she is often removed due to verbal and physical altercations.

CARLOS GRADE 4: He is one of five children in a two-parent, bilingual household in a rural community. He was diagnosed with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in kindergarten and takes medication for this condition. Carlos’s academic performance in early elementary school was strong, but he is having difficulty with the demands of the fourth-grade curriculum. His reading assessments show solid decoding skills, but his written work is often incomplete, and he has not mastered his math facts in spite of having good mathematical thinking skills. Carlos’s teachers feel that he is not putting enough effort into his work. Carlos has many friends, is a talented athlete in several youth sports, and is known as “LEGO® man” because he spends his free time building robots and inventing machines using LEGO and electronic parts.

AYANNA GRADE 6: She is one of two children in a single-parent, English-speaking family that recently relocated to a small town. Her mother reports that Ayanna was late in learning to talk in sentences and in learning to read. In second grade, she was diagnosed with a reading disorder and received small-group tutoring for two years to help her catch up. She decodes at grade level now and is not on an individualized education plan at her new school. Her teachers report that Ayanna is an attentive and highly organized student who puts tremendous effort into her work. However, she achieves little success except on memorization tasks. She recently won the schoolwide spelling bee. Though she decodes accurately and seems to listen in class, her notes and oral answers do not demonstrate good comprehension. Ayanna’s writing shows poor vocabulary, weak syntax, and difficulty staying on topic or elaborating on ideas, and her reading quiz scores are low. Ayanna also experiences social difficulty; her teachers note that she tries to fit in but is often ignored and sometimes teased by her peers.

ELIJAH GRADE 8: He is one of two foster children in a two-parent, English-speaking family in a mid-sized city. He has a history of being abused and in trouble with the law. Child services took custody of him when he was found living alone in a shack beside the rail tracks. His current living situation is his first foster placement, and it has been working out positively for close to two years. The quality of Elijah’s schoolwork varies from failing grades to perfect scores. He takes notes in class and participates in discussions, but completing homework is a major challenge. He sometimes falls asleep in class. He has difficulty deciding on writing topics and in organizing and elaborating on his ideas. His in-class test scores are generally very low, but longer-term projects are stronger if he remembers to do them. He has tremendous math anxiety and works at a very slow pace. Elijah’s oral language is marked by its slow pace, pauses, and frequent difficulty with word finding. He is a talented actor and musician.

JASON GRADE 10: He is one of four children in a single-parent, Spanish-speaking household in a large city. He is fluent in English. His teachers note that he seems to have a good understanding of concepts in the content areas based on the work he does in class, especially in math and chemistry. Though never a top student, Jason’s grades have been declining since he started high school. He is failing his classes because his test and essay scores are very low, and he is not doing homework consistently. Jason has a solid social group and occasionally participates in school activities when his work schedule allows it. Recently, he has expressed a desire to leave high school and pursue full-time work in the landscaping business he started with his older brother.

What to Do

No matter their grade level, the range of students’ skills and knowledge is dramatic. In order to nurture their educational lives, we need to know them well: where they come from and what their lives are like, what they like and dislike about school, and what they are good at and what they find difficult. We also need to learn about students’ language and literacy skills. Quite a few students enter our classrooms with individualized education plans (IEPs) in place, which provide clear guidance on the skills they need to develop and the accommodations and modifications we are required to provide. Most arrive without this guidance. What strategies can we use to gather useful information in a timely way?

Learning Questionnaires

Questionnaires are easy to design and can provide a wealth of information. Free online survey programs can be wonderfully helpful, but plain old pencil and paper work just as well. Many teachers use questionnaires at the beginning of each year or term to get specific information that will help guide their instruction. The questionnaires linked in the “Strategies to Download” section below provide teachers with immediate feedback on students’ perceptions of their academic strengths and needs in five areas: listening, speaking, reading, writing, and mathematics. Students’ perceptions alone are a rich source of diagnostic information. When compared with actual performance in class, students’ perceptions add insight into their self-awareness and self-efficacy. The questionnaires provide a good entry point for implementing formative assessment practices. They also provide a useful starting point for conferences with students or parents. They should not replace the formal diagnostic assessment tools to be used with students suspected of having learning disabilities.